Here's the story of my visit to the Minuteman Missile (MIMI) National Historic Site in South Dakota. It was after we'd finished our meetings on the Badlands/Pine Ridge visitor center. The Superintendent for MIMI had sat in on the last meeting and the two guys with me from HFC wasted no time buddying up to him and inviting him to lunch. Pretty soon, it was all set for us to visit the site. The guys managed to contain their excitement, barely.

Background: From 1963 to 1991, or thereabouts, 150 nuclear missiles stood ready for launch in western South Dakota. In each of 15 launch control facilities, two people sat ready, twenty-four/seven, to operate the missile controls. In 1991, the U.S. and Russia agreed to scale back on the whole "mutually assured destruction" thing. The missiles were removed and the silos destroyed: all but one. The 15 launch control facilities (LCFs) were emptied out. LCF Delta-01 and silo Delta-09 were given to the NPS. (Another LCF might become a bed and breakfast.)

Five hundred Minuteman III missiles remain active in Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota.

Outside the gate, MIMI's Superintendent told us what would've happened had we approached here when the site was operating. Think men with guns. The two folks on either side of the Superintendent are my colleagues from HFC. The guy on the right is the BADL Superintendent.

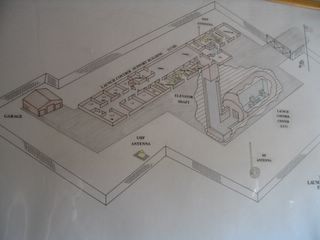

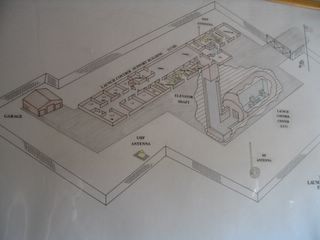

Here's a map of the launch control facility, with the gate through which we entered on the upper right. You can see the elevator shaft that goes to the underground launch control center, where two people sat with their fingers over the button (well, okay, more like 10,000 buttons and switches and keys and dials and...).

Inside the gate, there was a basketball hoop and the grown-over volleyball court you see here. You might think that thing on the right is a barbecue grill, but the US Airforce used it to burn secret codebooks every time the shift changed on the nuclear missile launchers.

The launch control facilities each had their own generators, in case the power failed. They also had industrial sized water and air filters, each housed in a separate room with only one entrance. All the facilities you can see above ground were dedicated to keeping the two people below ground secure from attack and functioning.

At each launch facility, the crew stayed for three days at a time. The two teams of launch commanders, the guys who worked down below, broke those three days up into 12-hour shifts. Off-duty, this was the only indoor gathering place for everyone. The Park set up the game of Battleship on the table.

The elevator down to the control room. It can only hold five or six people at a time, which is one reason the Park can only take a few visitors a day.

Take your pick: up or down. Check out the seventh item on the "don't forget" list for people coming off-shift.

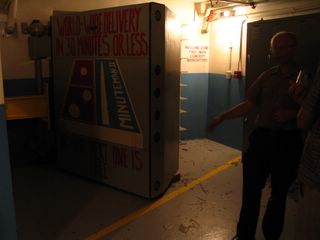

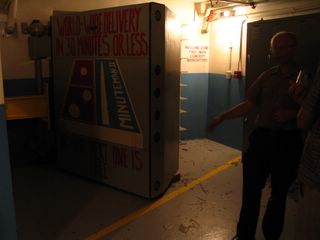

Here's the shot Waveflux has been waiting for. Apparantly, other launch facilities had images, too, but I can't find any pictures. The sign on the back wall, "NO-LONE ZONE," refers to the yellow line on the floor. No one was allowed to enter the control room by themselves. Had to be in pairs. Story goes, so the Superintendent was saying when I snapped the picture, that anyone crossing the yellow line alone could be shot. The launch commanders were armed.

And here it is. From 1963 to 1991, two people sat in this room at all times, with the ability to send nuclear missiles pretty much anywhere in the world. Well, actually, a third person was needed to launch: someone in "Looking Glass," one of the several aircraft that were constantly in flight, "mirroring" the control capacity of the command headquarters. In fact, if the room that you're looking into failed, someone on Looking Glass could launch every U.S. missile single-handedly. Shit.

The seat closer to the door was for the deputy commander. This was his station. The red box held the code books. There were about a million codes, I guess, all intended to assure that any launch command that reached this room was legitimate. The commanders all had their own locks and keys to that box, which they brought with them on duty.

This is the head guy's station. The map closest to you shows the other four "flights" (A, B, C, and E) that made up the squadron. If the other four launch control facilities were taken out, the guy at this seat could launch all their missiles, too.

The head. No, that's in the Navy. What is it in the Air Force? The can? The john? The crapper?

Instructions for launching a nuclear missile.

After all that technology, here's the pencil sharpener.

When we left the LCF, we drove 10 miles up I-90 toward Wall, SD, and stopped at the only remaining launch facility, i.e., missile silo. All the other 149 were imploded and filled with gravel and dirt, per the START treaty with the Russians. The pole on the left is part of a system to detect people approaching the silo. The nipple shape in the middle is the lid of an underground antenna, through which Looking Glass could send signals directly to the missile.

The cover over the silo, which is now 2/3 open, is that cow-catcher shaped thing on rails. The glass structure over it was built so people and Russian satellites can see down into the silo. The cover moved on rails to allow repair and replacement access to the missile, but, at launch, no one would wait for it to roll back. It was equipped with exploding bolts that would throw the cover off, towards us.

In all its phallic glory. Of course, it's been nipped - that cone no longer holds a bomb. See the cables attached at upper left? That "umbilical" carried the missile's instructions to it.

Here's a story about the four times the US and USSR came close to launching missiles.

Here's one about pranksters in the missile launch crew.

For lots of related historical images, go here.

Background: From 1963 to 1991, or thereabouts, 150 nuclear missiles stood ready for launch in western South Dakota. In each of 15 launch control facilities, two people sat ready, twenty-four/seven, to operate the missile controls. In 1991, the U.S. and Russia agreed to scale back on the whole "mutually assured destruction" thing. The missiles were removed and the silos destroyed: all but one. The 15 launch control facilities (LCFs) were emptied out. LCF Delta-01 and silo Delta-09 were given to the NPS. (Another LCF might become a bed and breakfast.)

Five hundred Minuteman III missiles remain active in Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota.

Outside the gate, MIMI's Superintendent told us what would've happened had we approached here when the site was operating. Think men with guns. The two folks on either side of the Superintendent are my colleagues from HFC. The guy on the right is the BADL Superintendent.

Here's a map of the launch control facility, with the gate through which we entered on the upper right. You can see the elevator shaft that goes to the underground launch control center, where two people sat with their fingers over the button (well, okay, more like 10,000 buttons and switches and keys and dials and...).

Inside the gate, there was a basketball hoop and the grown-over volleyball court you see here. You might think that thing on the right is a barbecue grill, but the US Airforce used it to burn secret codebooks every time the shift changed on the nuclear missile launchers.

The launch control facilities each had their own generators, in case the power failed. They also had industrial sized water and air filters, each housed in a separate room with only one entrance. All the facilities you can see above ground were dedicated to keeping the two people below ground secure from attack and functioning.

At each launch facility, the crew stayed for three days at a time. The two teams of launch commanders, the guys who worked down below, broke those three days up into 12-hour shifts. Off-duty, this was the only indoor gathering place for everyone. The Park set up the game of Battleship on the table.

The elevator down to the control room. It can only hold five or six people at a time, which is one reason the Park can only take a few visitors a day.

Take your pick: up or down. Check out the seventh item on the "don't forget" list for people coming off-shift.

Here's the shot Waveflux has been waiting for. Apparantly, other launch facilities had images, too, but I can't find any pictures. The sign on the back wall, "NO-LONE ZONE," refers to the yellow line on the floor. No one was allowed to enter the control room by themselves. Had to be in pairs. Story goes, so the Superintendent was saying when I snapped the picture, that anyone crossing the yellow line alone could be shot. The launch commanders were armed.

And here it is. From 1963 to 1991, two people sat in this room at all times, with the ability to send nuclear missiles pretty much anywhere in the world. Well, actually, a third person was needed to launch: someone in "Looking Glass," one of the several aircraft that were constantly in flight, "mirroring" the control capacity of the command headquarters. In fact, if the room that you're looking into failed, someone on Looking Glass could launch every U.S. missile single-handedly. Shit.

The seat closer to the door was for the deputy commander. This was his station. The red box held the code books. There were about a million codes, I guess, all intended to assure that any launch command that reached this room was legitimate. The commanders all had their own locks and keys to that box, which they brought with them on duty.

This is the head guy's station. The map closest to you shows the other four "flights" (A, B, C, and E) that made up the squadron. If the other four launch control facilities were taken out, the guy at this seat could launch all their missiles, too.

The head. No, that's in the Navy. What is it in the Air Force? The can? The john? The crapper?

Instructions for launching a nuclear missile.

After all that technology, here's the pencil sharpener.

When we left the LCF, we drove 10 miles up I-90 toward Wall, SD, and stopped at the only remaining launch facility, i.e., missile silo. All the other 149 were imploded and filled with gravel and dirt, per the START treaty with the Russians. The pole on the left is part of a system to detect people approaching the silo. The nipple shape in the middle is the lid of an underground antenna, through which Looking Glass could send signals directly to the missile.

The cover over the silo, which is now 2/3 open, is that cow-catcher shaped thing on rails. The glass structure over it was built so people and Russian satellites can see down into the silo. The cover moved on rails to allow repair and replacement access to the missile, but, at launch, no one would wait for it to roll back. It was equipped with exploding bolts that would throw the cover off, towards us.

In all its phallic glory. Of course, it's been nipped - that cone no longer holds a bomb. See the cables attached at upper left? That "umbilical" carried the missile's instructions to it.

Here's a story about the four times the US and USSR came close to launching missiles.

Here's one about pranksters in the missile launch crew.

For lots of related historical images, go here.

Comments

Post a Comment